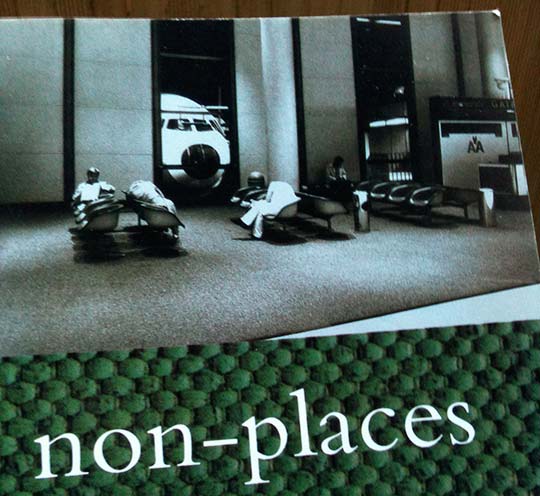

I recently finished reading “non-places: introduction to an anthropology of supermodernity” by Marc Augé. The book, recommended to me by Peter Lunenfeld, positions itself within anthropological thought and then uses that position to look at how we encounter, interpret, and analyze space.

My experience of the book was fragmentary; I read sections as I rode the bus, occasionally being forced to stop mid-sentence when I reached the last stop. This seemed like an appropriate way to encounter the material. As I passed through places marked only by signs, I was reading about their demarcation, the way they function as non-relational space. Unfortunately, it prevented me from effectively noting sections of the book; any attempt at writing was thwarted by the irregular vibrations of the bus. I’ll try to piece together some of the elements that interested me while I read, centered around the production of meaning for researchers and individuals.

The early portion of the book is dedicated to how anthropologists define the group which they are studying. Somehow, a relation between all group members must be found through discrete samples. This is no simple task, and takes consideration of the representativeness of sources and their reliability. Augé describes this world-building elegantly:

The field ethnologist’s activity throughout is the activity of a social surveyor, a manipulator of scales … [s]he cobbles together a significant universe by exploring intermediate universes at need. (Augé, 13)

All experience is fragmentary, and all places unfinished. Augé discusses this as a challenge when considering anthropological subjects, for cultures “never constitute finished totalities” and individuals “are never quite simple enough to become detached from the order that assigns them a position: they express its totality only from a certain angle.” (Augé, 22) We encounter the world as individuals, and we can present it to others only from our individual perspective. This presentation is one of the possible roles for an artist or maker. To establish a way for others to see the world from a new perspective, although they will not move entirely outside themselves.

A method for artists to present their world is suggested in the methods ethnologists use to discover worlds around them: the creation of intermediate universes, each of which clarifies some portion of the whole. This creation of universes can be used as a strategy for individual works, or thought of as a way of looking at an established artist’s ouvre. As a strategy for making work, I think it may be useful to consider the exhibition as a “significant universe” and the piece in it as intermediate ones. While the pieces all corroborate some whole, the gaps between them must be inferred by the audience. Viewers essentially study this universe and construct their own vision of what binds it together. I would also like to explore the possibility of creating a series of islands that inform each other, worlds in miniature, that constitute a single piece.

There are obviously many other facets of this short collection of essays. Eventually, I might like to take on the necessity of individual production of meaning as a reaction to the instability of collective reference points. Also, the notion of online locations as anthropological places, and how they exist as dynamic spaces theoretically without spatial borders, is worth addressing. Regarding online places, why is it that social networking sites don’t feel like they have a history when we return to them?

I am left with many questions right now, so I’ll include a few of them here: How do we create meaning for ourselves? How can we create spaces for the production of meaning? Places that are ready to be seeded with memories and relations.